|

from the Cambodia Daily, January 3-4, 2004

Fleeting Beauty

Book Recalls

Clothing, Cosmetics and

Personal Care in 19th and 20th Centuries

by MICHELLE

VACHON AND KUCH NAREN

In a

not-so-distant past beauty for a married Cambodian woman

meant blackening her teeth by chewing betel. Married women

with white teeth in the countryside would be criticized and

considered sickly pale.

Chewing

betel, which also reddens the lips, was supposed to keep

one's teeth clean and breath fresh. Women would apply wax on

their lips before ceremonies and special occasions to

prevent betel juice from running out of their mouths and

staining their clothes.

By the 1950s,

this habit had Men out of favor, especially in urban areas.

In the newly-independent country, students and government

workers opted to keep their teeth white.

In addition,

pitting—which a person chewing betel can hardly avoid, since

it makes one salivate—was prohibited in public places.

Today, only elderly women and a few men chew betel.

These are

some of the Cambodian customs mentioned in the book, "Seams

of Change," which will be released Tuesday at the opening of

an exhibition of clothes and objects at the Reyum Institute

of Arts and Culture. It was written by four archeology

graduates from the Royal University of Fine Arts who now

work as researchers for the institute.

As its

subtitle indicates, the 295-page book describes, in English

and in Khmer, "Clothing and the Care of the Self in Late

19th and 20th Centuries." The book is based on a series of

interviews with elderly Cambodians and includes descriptions

of clothes; sewing methods, patterns and tools; hair and

jewelry styles; and washing products for clothes and for

personal care.

The book is built on the memories of 40 people whose

recollections stretch nearly a century. The eldest

contributor is Pou Kech Lang, who was born in 1907 in Kandal

province. The youngest contributor, Lem Hok Cheang, was bom

in 1940 in Kompong Thorn province.

Previous

research on Cambodia's "official" history has focused on

personalities and political events, according to the

introduction written by Chea Narin, Chea Sopheary, Kem

Sonine and Preap Chanmara, authors of the book.

But "if we

want to know about everyday life and experiences of ordinary

people during this period, these official histories do not

offer us much information," they wrote.

For example,

old people sometimes talk about "wearing the water jar" or

the "tin gas tank," the authors said. These expressions

refer to the shortage of clothes and fabric during World War

II, when thread was requisitioned for the Japanese war

effort.

|

|

Courtesy of the Reyum Institute of Arts and Culture

Demonstrators show how women crushed seeds from the

jumpuh fruit to color their nails in the 1910s and

1920s. Women would do this only for their weddings

or special occasions. |

|

|

Some families

in remote areas had only one set of clothing for the whole

family, which one family member would wear to run errands

while the others hid, virtually naked, in the house. If a

visitor came while he and the clothes were away, one family

member would hide behind the gas can or sit in the water jar

while talking to the visitor.

The authors

discovered the origins of the expression "jip tong" by which

Cambodians sometimes call the popular rubber sandals with a

thong between the big and second toes.

|

|

|

|

(Left) Mrs

Mich, 88, shows Reyum researcher Chea Sopheary how to make a santeh shirt in

Kandal province last year. Traditionally cut from a single piece of cloth

without shoulder seams, this shirt was commonly worn by both men and women.

(Right)

An elderly woman from Siem Reap

province wears a traditional leak undershirt with pockets at the front—in the

past, women did not carry wallets or purses—and a sampot in the kben, or baggy

pants, style. |

Jip Tong was

the name of a factory known for its quality thongs, or

flip-flops, in the 1950s and 1960s. Cambodians also call the

sandals "ptoat" because they make a slapping sound and lift

dust when walking, the authors added.

The custom of

wearing shoes or sandals was introduced by the French in the

late 19th century, they said. Up until then, Cambodians had

gone barefoot However, while this new fashion was embraced

in the cities, it far from swept the countryside, as

80-year-old Ong Sok told the authors.

"When someone wore shoes [in the 1920s], my mother would

stare and criticize diem. People in our village [in Kandal

province] didn't wear them."

The first sandals in the countryside were made of palm tree

bark or roluos wood, with straps of vine or strips of

canvas, nylon bag or tire rubber, the authors said.

Some sandals

were constructed of thick pieces of wood, said 79-year-old

Sim Saren of Prey Veng province. "When there were fights,

they would use their shoes to hit each other on the head,"

he said. "So they stopped wearing thick shoes."

Shoe

factories appeared in the 1950s, and people switched to

manufactured shoes, said the authors. But poor farmers

continued to make their own for some time, buying one pair

of factory-made shoes for special occasions when they could

afford it, they said.

People also

made their clothes themselves with thread and needle; they

had few of them and had to make them last a long time.

"People

patched pants so many times, and wore them so long that they

became...just patches," said 88-year-old Mich of Kandal

province. People only had "two pairs of clothing for house

wear, two pairs of clothing for working, and two pairs of

clothing for ceremonial occasions," she said.

Since washing

aged fabric, people would just spread their clothes to let

the sweat evaporate and then store them, said Mich. In the

case of fine fabric, they would sprinkle the clothes with

water and carefully smooth and stretch them with their

hands, she said.

The section

of the book on undergarments shows camisoles that older

women still wear as blouses at home. In the past unmarried

women had to wear them very tight to flatten their chest the

ones who failed to do so were viewed with suspicion, said

the authors.

Numerous

customs involved people's hair, they said. Shortly after the

birth of the baby, a hair-cutting ceremony would be held to

announce his or her arrival in the world. At around age 13,

a child's head was shaved, leaving only a strand at the

front to mark puberty. The hair-cutting ritual still

performed at weddings today signifies mat the spouses are

entering a new phase of their lives.

Married women

wore their hair short, some of them only a few centimeters

long. Only unmarried women and women of Chinese background

wore long hair, usually tied in a bun.

For washing, people made ash soaps from various plants and

flowers, said the authors. Manufactured soaps and shampoos

became affordable to a larger number of people only in the

mid-1950s, the authors said.

|

|

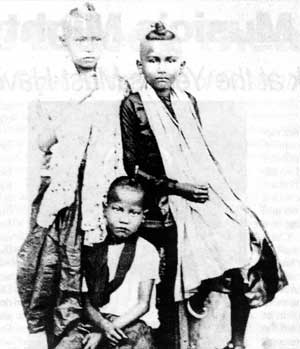

Courtesy of the Notional Archives of Cambodia

This photo, taken around the late 19th century,

shows children with their hair cut in the duk juk

style to show they had reached puberty. Their heads

were shaved except for a long strand in the center. |

|

|

This book

contains just a portion of the material accumulated by

Reyum's nine researchers. Two years ago, they started

interviewing more than 100 elderly people on all aspects of

life and customs in Cambodia and entering their

recollections in a database to preserve oral history in a

true "memory bank"

This had to

be done without delay, said Chea Sopheary. "I was afraid

that so much about the past would remain unknown or be lost

when those elderly people would pass away," she said.

'They were happy to talk when we asked about their daily

lives. They told us this was the first time they had a

chance to speak out".

As the

project evolved, Chea Narin, Chea Sopheary, Kem Son-ine and

Preap Chanmara became interested in the information they

were getting on clothes and personal care, and decided to

turn it into a book, Chea Narin said.

The book

shows the clothes and habits of ordinary people, she said.

"I had never seen or heard of some styles of clothes

described in the interviews, while others are still worn

today.

The long-tube

shirt, which was a long-sleeve tunic reaching below the

knees, used to be popular among women of all ages. Now, only

a few older women wear it for special occasions.

On the other

hand, a piece of others are stifl worn today." fabric, or

sampot, tied in the traditional kben style to form baggy

pants continues to be worn for ceremonies at the Royal

Palace, and Cambodian women regularly wear the sampot tied

in the samloy style as a long wraparound skirt.

During the

interviews, Kem Sonine was struck by the difference of

perception between elderly men and women. Since they were

kept at home to team household chores, women were not aware

of social problems, she said.

"They could

only answer questions regarding themselves or personal

matters," she said. Men, who as youths were sent to study at

the pagoda, had a much better understanding of social

issues, Kem Sonine said.

Based on

these findings, the four researchers want to explore

education and training practices in a second book, Chea

Sopheary said.

The

exhibition, which will run through March, will feature some

of the beauty products women made, such as the jumpuh fruit

used to color nails red and the tumeric powder they applied

to whiten and improve their skin.

Even though

rural women occasionally colored their lips or nails, they

generally used no makeup outside of ceremonies, the authors

said. A woman was valued for her competence in household and

domestic matters and not so much for her appearance, they

said.

The research

was funded by the Rockefeller Foundation, with additional

support from the Kasumisou Foundation and the Albert

Kunstadter Family Foundation.

|